Philadelphia Police: A History of Brutality

This post is part of Philly Power Research's “Beyond Policing” series. This series is continuing work that was previously led by Movement Alliance Project (MAP) over the past two years exploring how Philadelphia can invest in our communities to improve public safety instead of investing in policing. MAP's "Safety We Can Feel" campaign included a survey of 1300 Philadelphia residents and dozens of interviews on how to build strong, healthy, and safe communities.

content warning: This piece contains descriptions police brutality and newspaper photographs of victims of police brutality

Pictured: A poster by the Campaign Against Police Abuse that reads “Stop police abuse” across the bottom, below a broken nightstick and glasses. Above, many names of victims of police brutality are listed by year; from 1977 back to 1972, where the names abruptly cut off.

Throughout the history of the police department, Philadelphia police have used a variety of tactics to target, intimidate, and imprison Black, Brown, immigrant and working class Philadelphians, all while demanding more and more funding from the city at the expense of community services. For more than a century, the Philadelphia police have attacked and intimidated Black protesters, sided with white mobs, targeted Black individuals, disproportionately killed Black men, and failed to curtail officers' own dangerous behavior. Even as the city’s racial demographics have changed, “The police department overwhelmingly targets Black people — no matter the racial makeup of the city during any given period.”1

Police have historically sided against Black Philadelphians in times of racial upheaval and even directly attacked them. In 1838, when a white mob broke in and set fire to a meeting place for antislavery groups, watchmen did nothing to stop the violence or hold the mob accountable.2 Police confronted and shoved Black men standing in line to vote in 1870, and arrested those who complained.3 The following year, when Octavius Catto was assassinated, the police attacked Black voters.4 In 1918, Philadelphia Police sided with white mobs during race riots that ensued in part because a white mob attacked a Black woman for purchasing a home.5 Dr. Alexander Elkins summarized the racial dynamic of policing during these riots as, “All blacks had become rioters; all whites, police.”6 In the wake of the violence, T.D. Adkins, Pastor of Mt. Carmel Baptist Church at 58th and Race Streets wrote a letter to the editor at the Philadelphia Tribune: “Afro-Americans of this city are tired of legalized murder, we are sick at seeing death carried on by acts of legislation, we are heart-sick at seeing men killed with law, society outraged, morals underminded by law. [...] Let us proceed to organize at once.”7

In the years following the 1918 riots, the Philadelphia Tribune increasingly and vividly8 reported on police brutality9 and racial injustice. Jim Crow laws were still enforced by the state in northern cities well into the 20th century and the Tribune was often the only newspaper reporting and editorializing these stories. The paper’s committment to racial justice was reflected in its masthead, which declared: “Fighting against– Segregated schools; police brutality; economic and civic discrimination; racial treachery.”

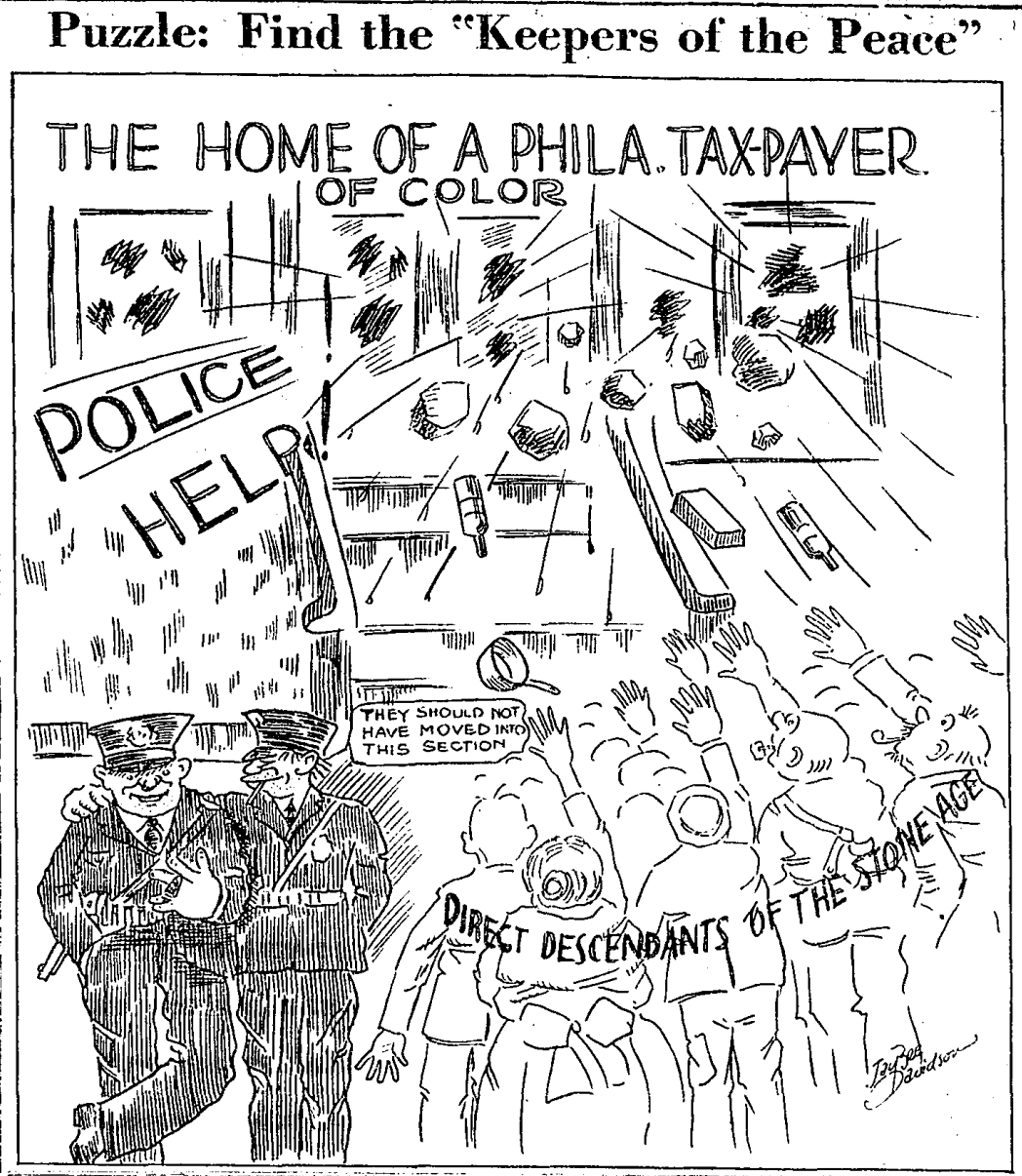

Pictured: A Philadelphia Tribune editorial cartoon titled “Puzzle: Find the 'keepers of the peace'” illustrates the idea that police protect only who they want to protect. A white mob (labeled “direct descendants of the stone age”) is attacking a house labeled “home of a Philadelphia tax payer of color.” Cries of “police, help!” come from the house while two police officers look the other way and say “they should not have moved into this section.” (Philadelphia Tribune, May 10, 1928)

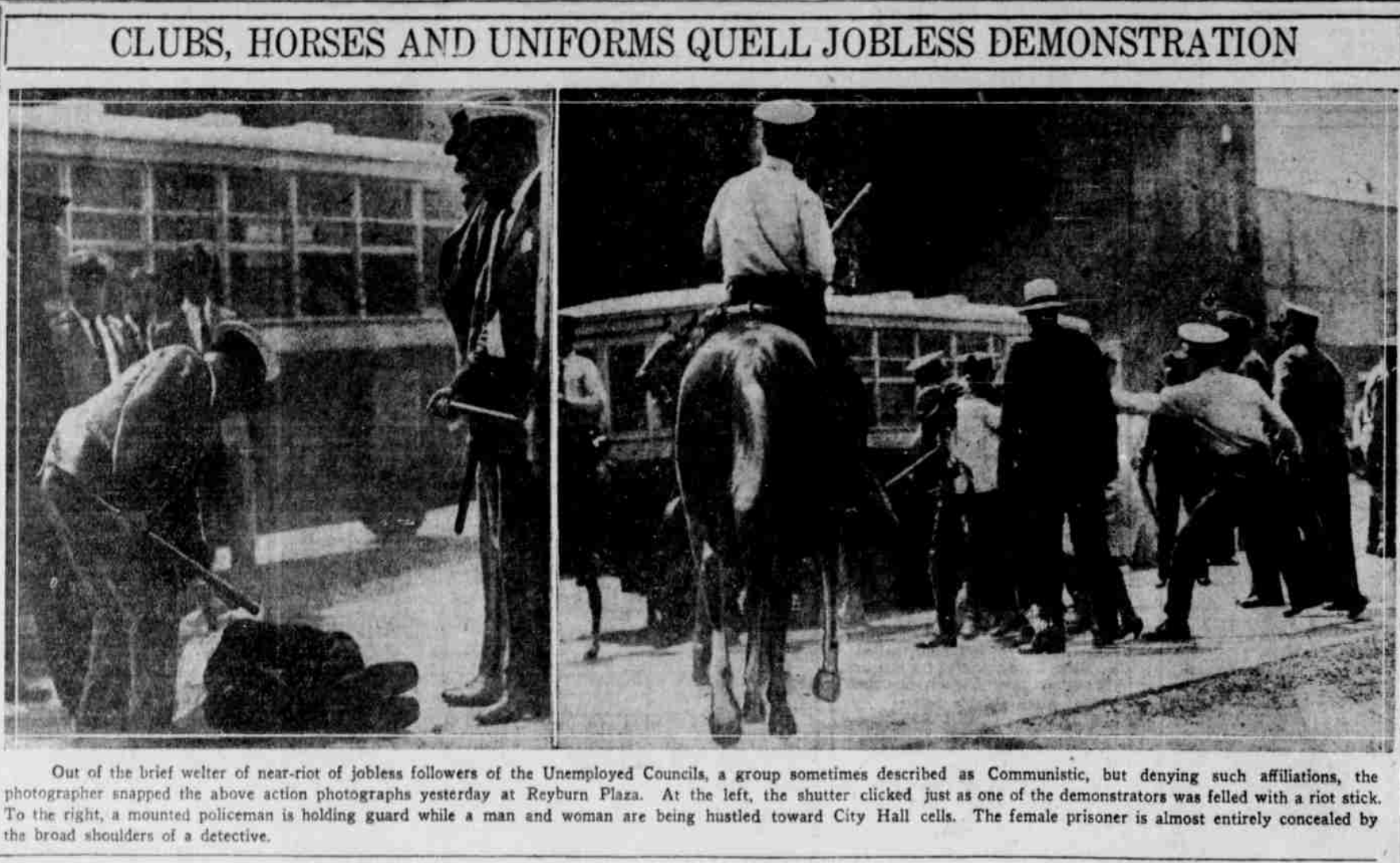

Through the Great Depression, Police violently suppressed demonstrations by multi-racial organizations of workers, labor unions, socialists and the unemployed. One such organization was the Northeast Unemployed Citizens League, formed by textile workers to organize against evictions and for food, pensions, and unemployment compensation.10 In 1932, a May Day march was planned, with participants marching from points across the city to Reyburn Plaza, just north of City Hall. Police violently put down the march; civilians and police were hospitalized, and two civilians were treated at St. Luke's Children’s Hospital for possible skull fractures.11 Allan G. Harper of the American Civil Liberties Union witnessed “inexcusable and unnecessary clubbing” by police, who apparently targeted Black demonstrators.12

On August 25, 1932, an estimated 1,500 marchers gathered at Reyburn Plaza to demand city relief money for the unemployed, the reopening of a homeless shelter, an eviction moratorium and tax relief for the working class.13 With demonstrators outside City Hall, Martin H. Powers of the Unemployed Council addressed members of City Council: “You councilmen may say that you can find no money to relieve the starving in this city, but you can find enough money, I see, to mobilize the entire police force to disperse and harass the 10,000 unemployed who are waiting there outside your windows.”14 Afterwards Director of Public Safety Kern Dodge utilized the familiar tactic of blaming “outside agitators” when he blamed the demonstration on “professional Communist agitators.”15 Hundreds were arrested and injured in the demonstration,16 which was later referred to as “The Battle of Reyburn Plaza.”

In 1946, when racially charged riots broke out between two high schools, police only arrested Black students and appeared to protect white boys.17 Later that same year, 25 organizations met in Philadelphia to plan for action against police terrorism of Black people. They resolved to focus on Philadelphia in particular, citing the railroading of Nick Williams, who was arrested and tried on 11 counts in just three hours. They also noted that Black veterans were frequently targeted by police.18 On November 16, 1947, police murdered two Black men on the same day in separate incidents– Raymond Crouser in South Philadelphia and Charles Fletcher in Germantown. The NAACP called an emergency rally to protest these killings19 and 1,200 people turned out to two mass demonstrations.20

The first federal indictment of Philadelphia Police officers on brutality charges was in 1950,21 when Issac Stedman and Marshal Gibson said that officers Herbert Winward and William McCloskey detained and abused them at a secluded location off Delaware Avenue.22 At the trial, Director of Public Safety Samuel H. Rosenberg and Assistant Superintendent of Police George Richardson both appeared as character witnesses, calling the officers “fine officers” and “good men as individuals.”23 The police officers were acquitted in 1951.24

Another precedent-setting federal police brutality case was brought in 1957,25 but was dropped by federal prosecutors a few months later.26 That same year, three allegedly drunk off-duty cops pulled James Lett out of his truck at Broad and Huntington. They began beating him and a bystander, James Ellerbee, came to his aid.27 Both Lett and Ellerbee were badly beaten,28 Lett was hospitalized for 19 days.29

Pictured: Philadelphia Tribune front page, June 29, 1957, reporting on multiple incidents of police misconduct. One story reports on police baseless police raids that targeted Black families in West Philadelphia and another graphically documented the police beating of James Lett.

In 1958, Philadelphia City Council held hearings on police brutality. Lett and many other Black Philadelphians testified about how they had been terrorized by police.30 The officers who had beaten Lett and Ellerbee were fired,31 and attempted to get their jobs back,32 but were apparently not prosecuted. In the 1950s, Police Commissioner Thomas J. Gibbons responded to allegations of police brutality by claiming that new recruits were given training in “race relations.”33 During Gibbons’s tenure the police began using “shotgun squads”– patrol vehicles where an officer would brandish a shotgun out the window as a show of force.34

On June 4, 1960, police arrived at the scene of an altercation with a report of shots fired on the 2200 block of N. 17th Street. Emmanuel Thomas ran to the steps of his neighbor, Louise Jones, and Officer Robert Marinelli fired wildly out the window of his police van onto the crowded street, killing Emmanuel Thomas and Louise Jones, who was just inside her front door. Shots also grazed the neck of a bystander and hit books held by a nearby teenager.35 Officer Marinelli claimed that he thought Thomas had a gun.36 In reality, both victims were unarmed. Following the killings, police supervisors said Marinelli “acted in good faith.”37 Jones's mother, Mrs. Ella Louise Jones, died shortly after learning her daughter had been killed.38 Marinelli was later indicted, and the Fraternal Order of Police paid his full salary while he waited for trial.39

Days later, over 700 people attended a mass meeting at Jones Memorial Baptist Church to discuss the killings, plan a response and demand action from the City Council.40 Over 4,500 mourners attended the joint funeral service for Ella Lucy Jones and Louise Jones at New Thankful Baptist Church. Not a single city official attended.41 After the service, 150 cars and the hearses carrying the bodies of the victims circled City Hall at least a dozen times, while over 100 protestors picketed City Hall on foot, with some signs that read “Vote Dilworth Out,” “Am Cop, Have Gun, Will Shoot,” and “Stop Police Brutality.”

After almost a year of delays, the trial of Officer Robert Marinelli began in June of 1961. If convicted, it would be the first time in Philadelphia history that a white cop would be convicted for killing a Black person.42 During the trial, Marinelli testified that Thomas was in a “crouching, menacing” position and claimed that he “feared for his life.” Police inspector John J. Kelly testified that he or another officer would’ve done the same. The all-white jury composed of ten women and two men deliberated for only 1 hour and 35 minutes before they found Marinelli not guilty on all charges.43 The North Philadelphia Committee for Equal Justice organized protests that descended on City Hall. William Lane of the committee said, “Police brutality exists because the city policy makers have approved it, this is best demonstrated by the Marinelli case– they moved quickly to sanction his crime, to guarantee him no loss of pay or dismissal– and to perpetuate a joke for a trial.”44 Robert Marinelli was given a job as a clerk in the records department at City Hall.45

Philadelphia’s most well known era of conspicuous police brutality was during Frank Rizzo’s tenure as police commissioner and later as mayor. Rizzo was promoted to deputy police commissioner even though the NAACP characterized his “storm trooper tactics”46 against Black communities. On December 24, 1963, the Inquirer reported that Police Commissioner Howard Leary and Mayor James Tate had ignored the history of Rizzo’s racist brutality and promoted him anyway.47 During his time as police commissioner from 1967-1971, Frank Rizzo’s police department attacked protesting school children with dogs, used extreme tactics against protestors, and raided his political enemies. After years of cultivating a ruthless "law and order" image as police commissioner, Rizzo was elected mayor, with the backing of outgoing mayor James Tate and the Democratic Party. As mayor from 1972-1980, these behaviors continued, many Philadelphia communities were alienated, and the police budget increased.48

In the 1970s, the Coalition of Organizations on Philadelphia Police Accountability and Responsibility (COPPAR) urged the City Council and the District Attorney to address police brutality.49 In the wake of the killing of Raymond Brooks by Officer Richard Carter, COPPAR chair Mary Rouse asked for a grand jury investigation: “Police have too frequently gotten away with literal murder. It is high time that a full-fledged investigation be made of the operations of the Philadelphia Police Department and of the procedures by which it justifies a murder of a civilian by a policeman.”50 By 1976, Philadelphia Police brutality made it to the US Supreme Court. In a 5-3 decision, the court struck down an earlier District Court order that would’ve forced the Philadelphia Police Department to use strict protocols for handling citizen complaints of police brutality. The district court order was the result of two police brutality lawsuits– in one suit, Gerald Goode, was beaten by officers Anthony DeFazio and John D’Amico after questioning their handling of a Black suspect; in another, COPPAR claimed that the police department under Frank Rizzo had established a pattern of brutality against Black Philadelphians in general, and specifically targeted members of the Black Panther Party.51

Pictured: A poster by the Campaign Against Police Abuse that reads “Stop police abuse” across the bottom, below a broken nightstick and glasses. Above, many names of victims of police brutality are listed by year; from 1977 back to 1972, where the names abruptly cut off.

Black Philadelphians have consistently been disproportionately targeted by police, arrested, and jailed. W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1899 book The Philadelphia Negro found that before the Civil War, Black people were 5% of the city population but almost a third of the jail population.52 A 1926 study by social worker Anna J. Thompson found that one third of all Black residents arrested by police were released with no charge due to lack of evidence.53 Black men accounted for 20.5% of arrests while being only 3.7% of the total population. Black women were 48% of the population of the county’s female penal and correctional institutions while being only 7.3%54 of the total female population.55 And today, things have not changed much. In the face of a 48.5% decrease in the overall Philadelphia jail population from July 2015 to September 2020, the proportion of Black incarcerated individuals actually increased from 67.5% to 73.3%,56 despite only making up about 43% of the Philadelphia population.57

This targeting by police extends directly to how Black Philadelphians have been treated at the hands of police. In 1952, a University of Pennsylvania Law Review article said that Black Philadelphians who “assert their rights against the police apparently do so in some cases at the risk of arrest”– rights which included “inquiring why a friend was in the police wagon.”58 A 1957 study found that over half of the white officers “found it necessary to be more strict” with “law violators” who were Black than white.59 Black pedestrians and drivers alike are more often stopped than others; in the first half of 2019, Black drivers accounted for 74% of all vehicle stops and 80% of searches.60

Black Philadelphians have long been the majority of victims of police violence. The Philadelphia Inquirer’s timeline of police violence against Black Philadelphians includes many instances of police murders: the shooting of Henry Truman in 1870, the in-custody death of Riley Bullock in 1918, the shooting of Willie Philyaw in 1963, the shooting of 16-year-old Michael Sherard in 1976, the shooting of 19-year-old Michael Carpenter in 1978, the shooting of Nelson Artist in 1978, the shooting of Winston C. X. Hood, Jr. in 1978, the shooting of Cornell Warren in 1978, the shooting of 17-year-old William H. Green in 1980 (after Mayor William Green imposed new rules on deadly force), the shooting of Charles Janerette in 1984, the beating of Michael Grant in 1991, the shooting of Charles Matthews in 1992, the shooting of 18-year-old Donta Dawson in 1998, 22 shooting deaths in 2006, the shooting of 15-year-old Ronald Timbers in 2007, the shooting of Abebe Isaac in 2008, the shooting of Jamil Moses in 2011, the shooting of Christopher Sowell in 2016, the shooting of David Jones in 2017, the shooting of Dennis Plowden, Jr. in 2017, and the shooting of Walter Wallace, Jr. in 2020.61 Only two officers have ever been convicted in connection with these deaths.62

Multiple studies throughout the past several decades document the racial disproportionality of police shootings as well. A 1963 study on lethal police force found that between 1950 and 1960, 87.5% of police shooting victims were Black, despite only making up 22% of the population.63 A 1979 study found that between 1970 and 1978 there were 469 police shootings, and two thirds of police shooting victims in 1978 were Black.64 In 2015, the Department of Justice found the police in Philly shoot Black people at twice their proportion of the population - Black people make up 41% of the population but 80% of those shot by police over the prior six years.65 Even more significantly, police shootings rose even when crime fell.66

The Philadelphia Police Department is also responsible for the infamous bombing of MOVE, a Black liberation and naturalist organization. On May 13, 1985, Philly police dropped a C-4 explosive from a PA State Police helicopter on the MOVE organization at 6221 Osage Avenue.67 The resulting fire was allowed to burn, as the Police Commissioner “asked fire officials to allow flames to rage unimpeded.”68 The bombing and fire killed eleven people, including five children, and destroyed 61 homes, leaving more than 250 people homeless.69

The police have not changed their behavior and still push for expansion, despite leadership claiming to curtail their power or enact reforms– as seen through the history of stop and frisk. In 1985 the police began “Operation Cold Turkey,” which stopped, searched, and questioned 1,500 people without cause.70 In 2007, Michael Nutter campaigned for mayor promising to expand stop-and-frisk. A federal lawsuit in 2010 found a pattern of police disproportionately stopping and frisking Black and Latinx people.71 In 2015, Mayor Jim Kenney campaigned on promising to end it. As of 2020, stop-and-frisk continued in Philadelphia,72 and now, unconstitutional stops have been banned as part of a November 2020 ballot initiative that passed in the recent general election.73

During racial justice protests in 2020, Philadelphia Police indiscriminately fired tear gas in residential neighborhoods and beat, tear gassed, and used dogs on protesters.74 In October 2020, police shot and killed Walter Wallace, a Black West Philadelphian in the midst of a mental health crisis; in response to outrage and grief, Police Commissioner Outlaw implied the department needed even more funding for widespread deployment of tasers and de-escalation training.75 City Council leadership was quick to offer the police department $9.5 million for “non-lethal weapons,” even though Wallace’s family called 911 for emergency ambulance services, not police, meaning the officers should not have been present at all, with or without tasers.76

Most recently, in 2022 police shot 12 year old Thomas Sidero in the back, killing him in South Philly. The police narrative of the incident conflicted with the incident as recounted by Sidero’s friend who witnessed the incident. While police refused to name the officers involved, their names were printed in reporting by the Philadelphia Inquirer. None of the officers were wearing body cameras.77

Attempted reforms

The response to police misconduct and violence is often some attempt at policy reform, such as increasing training and transparency, or increasing the police budget to buy more equipment, like body worn cameras, tasers, or other technologies that developers claim reduce police violence. However, the reform measures implemented in the past have not materially changed the power the police have or the violence they perpetuate on Black communities. One thing these measures do have in common is that they are minor reforms with a major monetary cost to the city.

Implementing and maintaining reforms in police departments is difficult, if not impossible. Like any massive change, it requires the buy-in of those who must implement the new practices on the ground. One study found that a police officer subculture that resists policy changes is a major factor in reforms failing to succeed and endure.78 Another article found that even when police departments hire consultant after consultant and implement their recommended data-driven models, the reforms don’t stick because of the bureaucracy and lack of support from the city and police unions.79

Another scholar studied 11 reasons why police reforms tend to fail, from resistance by managers through rank-and-file officers to resistance from the local police union.80 And in Philly, our local police union is notoriously resistant to reforms that curtail their power in any way81 or that impose non-police led oversight.82

Further, as author Mychal Denzel Smith argues, reforms can't fix the underlying issues baked into policing and police department culture, and celebrating these tiny changes as good progress gets in the way of meaningful big change: “Incremental change keeps the grinding forces of oppression—of death—in place.”83

Prior Reforms

One key reform that has come up in the wake of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of former police officer Derek Chauvin is the importance of civilian complaints and removing officers with long records of misconduct from the force. However, it “remains notoriously difficult in the United States to hold officers accountable” for their misdeeds, even when they commit violence against community members.84 Even with the election of a person people have termed a progressive prosecutor in Larry Krasner and with a new “change-oriented police chief” in Philly, we have still “struggled to punish or remove bad actors.”85

Civilian complaints like those against Chauvin are often ignored or don’t result in change, even for officers with a long track record of complaints. According to a report by the Philly Police Advisory Commission,86 less than 1% of the over 3,500 citizen complaints filed against the Philly Police between 2015 and 2020 actually resulted in formal disciplinary action, despite the majority of complaints being investigated. Most complaints were not sustained. Of those complaints that were sustained, only 2% were found guilty, only 0.5% resulted in at least a one day suspension, and the most severe discipline was just a 30 day suspension. Almost 75% of the sustained complaints were not even heard by the Police Board of Inquiry to evaluate guilt - instead involved officers just received training and counseling. Police-involved domestic violence is an especially egregious issue in which complaints are not taken seriously: one Philly officer received five complaints in four years but only one was sustained, and another officer stayed on the job through 18 months and three complaints of harassment.87

In the unlikely event that police officers do face real consequences for their actions and even lose their jobs due to misconduct, police have a notoriously robust appeals and arbitration process - meaning they can often get their jobs back even if they are found guilty, The Inquirer analyzed 170 cases of police arbitration from 2011-2019 and found that police had their discipline overturned or reduced through arbitration a striking 70% of the time.88 Six PPD officers were charged with domestic violence over the course of one year; all appealed and several were likely to get their jobs back,89 especially since officers are deliberately only charged with disorderly conduct rather than domestic violence, so they are allowed to come back to work.90 Even when the PPD’s Internal Affairs Division builds a case against a police officer, and even when, as in one case, the arbitrator involved states that the officer “needs to behave better” than burglary, trespass, and theft, dismissal is determined to be “too extreme” in favor of anger management classes and an expunged record.91

Another frequently cited reform is the civilian oversight boards described above. Philadelphia’s police department has, at least until now, mostly avoided meaningful community oversight or civilian review. The PPD implemented The Use of Force Review Board in 2015 to “maintain Departmental integrity and ensure the public is properly protected” by reviewing all police-involved shootings and incidents where “extraordinary and unanticipated actions were required” to protect police, suspects, and others.92 This review board only has the power to give administrative approval or disapproval that an officer’s actions were (or were not) in accordance with departmental policy, tell an officer they need to improve their tactics and decision making, or decide there was a training issue or a non use of force violation.93 As of November 2020, this board had not convened in over a year, and as many as 25 police shootings were still awaiting review.94

As we’ve seen in our analysis of the history of police corruption in Philadelphia, we see a similar failure pattern with “attempts” to end police brutality. Throughout the history of the police department, city officials have tried similar reforms over and over again, each time expecting a different result. For 70 years and counting we’ve been told that officers can be trained to be less brutal and less racist. While the costs of police technology and training go up, police brutality continues. While communities don’t have control of the police and citizens' basic needs are unmet, police brutality continues. The City Council and the Mayor can choose to provide people the resources they need and begin to obviate the need for police.

References

-

https://momentum.medium.com/philadelphia-is-fed-up-463553a98dbc ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

"WHITE POLICEMAN CLUBS A RACE RIOT VICTIM ON HOSPITAL COT” Philadelphia Tribune (1912-2001), Aug 10, 1918. https://search.proquest.com/docview/530774042.

G, Grant Williams. "SCHNEIDER IS IN THE JAIL HOUSE NOW: PRISONER HELD BULLOCK WHILE RAMSEY SHOT HIM" Philadelphia Tribune (1912-2001), Sep 28, 1918. https://search.proquest.com/docview/530774679. ↩

-

Elkins, Alexander. "At Once Judge, Jury, and Executioner”: Rioting and Policing in Philadelphia, 1838-1964." Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 54 (Spring 2014): 67-90. ↩

-

Adkins, T. D. "PHILADELPHIA GRIPPED BY A RACE RIOT." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Aug 10, 1918. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/philadelphia-gripped-race-riot/docview/530779130/se-2. ↩

-

"Police Brutality Victims." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 19, 1930. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/police-brutality-victims/docview/531005823/se-2. ↩

-

"A Sample of Police Brutality." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), May 30, 1929. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/article-1-no-title/docview/531002487/se-2. ↩

-

https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/great-depression/ ↩

-

"May 1, 1932 (Page 1 of 118)." Philadelphia Inquirer (1860-1934), May 01, 1932. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/may-1-1932-page-118/docview/1831405865/se-2. ↩

-

"May 1, 1932 (Page 11 of 118)." Philadelphia Inquirer (1860-1934), May 01, 1932. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/may-1-1932-page-118/docview/1831405865/se-2. ↩

-

"August 26, 1932 (Page 1 of 24)." Philadelphia Inquirer (1860-1934), Aug 26, 1932. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-26-1932-page-1-24/docview/1831403458/se-2. ↩

-

"August 26, 1932 (Page 4 of 24)." Philadelphia Inquirer (1860-1934), Aug 26, 1932. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-26-1932-page-1-24/docview/1831403458/se-2. ↩

-

"August 27, 1932 (Page 3 of 20)." Philadelphia Inquirer (1860-1934), Aug 27, 1932. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-27-1932-page-3-20/docview/1831406487/se-2. ↩

-

Ryan, Francis. AFSCME's Philadelphia story : municipal workers and urban power in the twentieth century, p. 58, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA. 2011 ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

"25 Organizations Meet to End Police Terrorism." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 01, 1946. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/25-organizations-meet-end-police-terrorism/docview/531784302/se-2. ↩

-

"Rap Cop on Quick Trigger." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Nov 25, 1947. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/rap-cop-on-quick-trigger/docview/531799663/se-2. ↩

-

"IRATE NEIGHBORS PUSH YOUTH'S SLAYING PROBE: CRITICIZE GUN-HAPPY POLICE." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Nov 29, 1947. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/irate-neighbors-push-youths-slaying-probe/docview/531835693/se-2. ↩

-

"Police Brass Uphold Cops Accused of Prisoner Assault." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jan 13, 1951. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/police-brass-uphold-cops-accused-prisoner-assault/docview/531912668/se-2. ↩

-

"September 8, 1950 (Page 1 of 60)." The Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger (1934-1969), Sep 08, 1950. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/september-8-1950-page-1-60/docview/1837528960/se-2. ↩

-

"Police Brass Uphold Cops Accused of Prisoner Assault." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jan 13, 1951. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/police-brass-uphold-cops-accused-prisoner-assault/docview/531912668/se-2. ↩

-

"January 13, 1951 (Page 18 of 88)." The Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger (1934-1969), Jan 13, 1951. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/january-13-1951-page-18-88/docview/1835127523/se-2. ↩

-

"Two Police Brutality Cases Slated For Grand Jury." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 04, 1957. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/two-police-brutality-cases-slated-forr-grand-jury/docview/532143361/se-2. ↩

-

"October 31, 1957 (Page 29 of 40)." The Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger (1934-1969), Oct 31, 1957. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/october-31-1957-page-29-40/docview/1835914975/se-2. ↩

-

Rolen, Ruth. "Victims of Police Brutality Freed, Judge Throws Case Out." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jan 10, 1959. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/victims-police-brutality-freed-judge-throws-case/docview/532337300/se-2. ↩

-

Anderson, Dorothy. "BLAST COP BEATINGS: 3 POLICEMEN GOING BEFORE TRIAL BOARD." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 29, 1957. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/blast-cop-beatings/docview/532079445/se-2. ↩

-

Anderson, Dorothy. "POLICE ACTS SHOCK COUNCILMEN: MEN AND WOMEN SOB OUT STORIES OF BAD BEATINGS AND RAIDS." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jan 21, 1958. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/police-acts-shock-councilmen/docview/532174512/se-2. ↩

-

Anderson, Dorothy. "POLICE ACTS SHOCK COUNCILMEN: MEN AND WOMEN SOB OUT STORIES OF BAD BEATINGS AND RAIDS." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jan 21, 1958. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/police-acts-shock-councilmen/docview/532174512/se-2. ↩

-

Anderson, Dorothy. "3 COPS FIRED FOR BEATING NEGRO: 3 POLICEMEN FIRED FOR BEATING NEGRO." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Sep 21, 1957. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/3-cops-fired-beating-negro/docview/532161506/se-2. ↩

-

Anderson, Dorothy. "Cops Fired for Beating Negro Trying to Regain their Jobs." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Nov 23, 1957. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/cops-fired-beating-negro-trying-regain-their-jobs/docview/532119624/se-2. ↩

-

"Gibbons, Says He'll Take Swift Action Against Complaints." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Nov 25, 1952. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/gibbons-says-hell-take-swift-action-against/docview/532000331/se-2. ↩

-

"November 21, 1954 (Page 41 of 238)." The Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger (1934-1969), Nov 21, 1954. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1836417221. ↩

-

"To Arrest Officer Who Shot, Killed 2 without Warning: Mothers, Children Dove for Cover to Escape Deadly Hail of Bullets." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 07, 1960. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/arrest-officer-who-shot-killed-2-without-warning/docview/532241870/se-2. ↩

-

"Protest Follows Cop Shooting in which 4 Died." Afro-American (1893-), Jun 18, 1960. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/protest-follows-cop-shooting-which-4-died/docview/532028697/se-2. ↩

-

"To Arrest Officer Who Shot, Killed 2 without Warning: Mothers, Children Dove for Cover to Escape Deadly Hail of Bullets." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 07, 1960. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/arrest-officer-who-shot-killed-2-without-warning/docview/532241870/se-2. ↩

-

"Protest Follows Cop Shooting in which 4 Died." Afro-American (1893-), Jun 18, 1960. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/protest-follows-cop-shooting-which-4-died/docview/532028697/se-2. ↩

-

"Patrolman, Who Shot 2 Innocent Persons to Death, Gets 4-Month Vacation with Pay as His 'Reward': Take Marriage Vows but Victims' Relatives can't Collect Anything for Funerals Increase Tensions in North Phila. Area Where Incident Occurred." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 11, 1960. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/patrolman-who-shot-2-innocent-persons-death-gets/docview/532245000/se-2. ↩

-

"BLAST KILLINGS AT MASS MEETING: SPEAKERS URGE WITNESSES "TO COME FORWARD" OVERFLOW CROWD VOWS TO FIGHT POLICE BRUTALITY." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 07, 1960. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/blast-killings-at-mass-meeting/docview/532182467/se-2. ↩

-

"150 Cars, Hearses Circle City Hall; Protest Killings: Broad St. Traffic Tied Up as Groups Plead for Justice." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 14, 1960. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/150-cars-hearses-cirle-city-hall-protest-killings/docview/532376988/se-2. ↩

-

"Officer could Get 10-20 Years if Rap Sticks: Conviction would Mark First Time for Killing Negro." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 11, 1960. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/officer-could-get-10-20-years-if-rap-sticks/docview/532229072/se-2. ↩

-

Gray, Peyton. "Jury 'Only' Takes 95 Minutes to Free Officer Marinelli of all Charges." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 10, 1961. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/jury-only-takes-95-minutes-free-officer-marinelli/docview/532268066/se-2. ↩

-

Farmer, Leroy. "N. Phila. Protests Marinelli Trial 'Whitewash';Vows to Continue Fight: Equal Justice Committee Memorializes Victims with Mass Meeting, Motorcade Around City Hall." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 13, 1961. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/n-phila-protests-marinelli-trial-whitewash-vows/docview/532402184/se-2. ↩

-

Gray, Peyton. "Jury 'Only' Takes 95 Minutes to Free Officer Marinelli of all Charges." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), Jun 10, 1961. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/jury-only-takes-95-minutes-free-officer-marinelli/docview/532268066/se-2. ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6986034-Black-and-Blue-Articles.html#document/p13 ↩

-

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/kwxp3m/remembering-frank-rizzo-the-most-notorious-cop-in-philadelphia-history-1022 ↩

-

Geller, Laurence. "Stop Police from Shooting Fleeing Suspects, 21 Groups Urge City Council." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-), May 19, 1970. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/stop-police-shooting-fleeing-suspects-21-groups/docview/532585256/se-2?accountid=10977. ↩

-

"January 17, 1971 (Page 15 of 280)." Philadelphia Inquirer (1969-2001), Jan 17, 1971. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/january-17-1971-page-15-280/docview/1842733392/se-2?accountid=10977. ↩

-

"January 22, 1976 (Page 1 of 40)." Philadelphia Inquirer (1969-2001), Jan 22, 1976. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/january-22-1976-page-1-40/docview/1842945518/se-2?accountid=10977. ↩

-

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Philadelphia_Negro/qqkJAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover ↩

-

Karl E. Johnson. “Police-Black Community Relations in Postwar Philadelphia: Race and Criminalization in Urban Social Spaces, 1945-1960.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 89, no. 2, 2004, pp. 118–134. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4134096. Accessed 3 Sept. 2020. ↩

-

Digitally transcribed by Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Edited, verified by Michael Haines. Compiled, edited and verified by Social Explorer.. Race By Sex, 1920. Prepared by Social Explorer. https://www.socialexplorer.com/data/Census1920/metadata?ds=SE&table=T15 (accessed 19 February 2022, 21:42:39 GMT-5). ↩

-

Karl E. Johnson. “Police-Black Community Relations in Postwar Philadelphia: Race and Criminalization in Urban Social Spaces, 1945-1960.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 89, no. 2, 2004, pp. 118–134. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4134096. Accessed 3 Sept. 2020. ↩

-

https://www.phila.gov/media/20201021134342/Full-Public-Jail-Report-September-2020.pdf ↩

-

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/philadelphiacountypennsylvania ↩

-

https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8018&context=penn_law_review ↩

-

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015020699974&view=1up&seq=123 - p. 116 ↩

-

https://momentum.medium.com/philadelphia-is-fed-up-463553a98dbc ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

https://momentum.medium.com/philadelphia-is-fed-up-463553a98dbc ↩

-

Robin, Gerald D. “Justifiable Homicide by Police Officers.” The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science 54, no. 2 (1963): 226. ↩

-

Deadly Force Report. Public Interest Law Center, 1979. ↩

-

https://momentum.medium.com/philadelphia-is-fed-up-463553a98dbc ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/10/move-1985-bombing-reconciliation-philadelphia ↩

-

https://www.nytimes.com/1985/10/19/us/philadelphis-chief-says-he-wanted-fire-to-burn.html ↩

-

https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/8/8/20747198/philadelphia-bombing-1985-move ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html ↩

-

https://whyy.org/articles/philly-civil-rights-groups-demand-that-the-mayor-end-stop-and-frisk/ ↩

-

https://billypenn.com/2020/10/06/philadelphia-stop-frisk-abolish-police-search-racism-bias-aclu/ and https://ballotpedia.org/Philadelphia,_Pennsylvania,_Question_1,_Call_on_Police_to_End_Unconstitutional_Stop-and-Frisk_Amendment_(November_2020) ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/crime/a/west-philadelphia-52nd-street-protest-police-response-tear-gas-20200717.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia/live/philadelphia-protests-police-shooting-walter-wallace-jr-20201027.html#card-410430166 and https://twitter.com/PHLPublicHealth/status/1321134279951216641 (~53 min) ↩

-

https://www.phillytrib.com/news/local_news/city-council-looks-to-boost-police-funding-to-purchase-tasers/article_82bd624a-f8d6-53a9-bd98-8ce601532e11.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-police-shooting-thomas-siderio-officers-20220303.html ↩

-

https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1106&context=plr ↩

-

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2019/02/13/marshall-project-more-cops-dont-mean-less-crime-experts-say/2818056002/ ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/pennsylvania/philadelphia-police-union-reform-george-floyd-fop-john-mcnesby-20200619.html ↩

-

https://whyy.org/articles/will-phillys-new-police-reforms-work-experts-say-the-evidence-is-mixed/ ↩

-

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/09/police-reform-is-not-enough/614176/ ↩

-

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/30/us/derek-chauvin-george-floyd.html ↩

-

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/30/us/derek-chauvin-george-floyd.html ↩

-

https://whyy.org/articles/report-less-than-1-of-civilian-complaints-filed-against-philly-police-result-in-discipline/ ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-police-union-contract-domestic-violence-fired-20200228.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/a/philadelphia-police-problem-union-misconduct-secret-20190912.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-police-union-contract-domestic-violence-fired-20200228.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-police-union-contract-domestic-violence-fired-20200228.html ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/a/philadelphia-police-problem-union-misconduct-secret-20190912.html ↩

-

https://www.phillypolice.com/assets/directives/D10.4-UseOfForceReviewBoard.pdf ↩

-

https://www.phillypolice.com/assets/directives/D10.4-UseOfForceReviewBoard.pdf ↩

-

https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-police-shootings-use-force-review-board-officers-danielle-outlaw-20201123.html ↩

This post is part of Philly Power Research's “Beyond Policing” series. This series is continuing work that was previously led by Movement Alliance Project over the past two years exploring how Philadelphia can invest in our communities to improve public safety instead of investing in policing. MAP's "Safety We Can Feel" campaign included a survey of 1300 Philadelphia residents and dozens of interviews on how to build strong, healthy, and safe communities.